[10 minute read]

In late June 2020, travel restrictions within the borders of South Australia were lifted. We could now travel within our beautiful state of South Australia. Loading up the car we headed up to Burra, a heritage mining and pastoral town in the states’ Mid-North. Ahead of us was five days reunited with life in hotels, restaurants, heritage walks and meeting new and interesting people.

Keeping our hands to ourselves, always rubbed up with hand-sanitiser, we maintained a one kangaroo distance between others, booked well ahead for meals, and enjoyed cellar door wine tasting seated at tables. It was an eye in to the future world of travel in the post-Corona era.

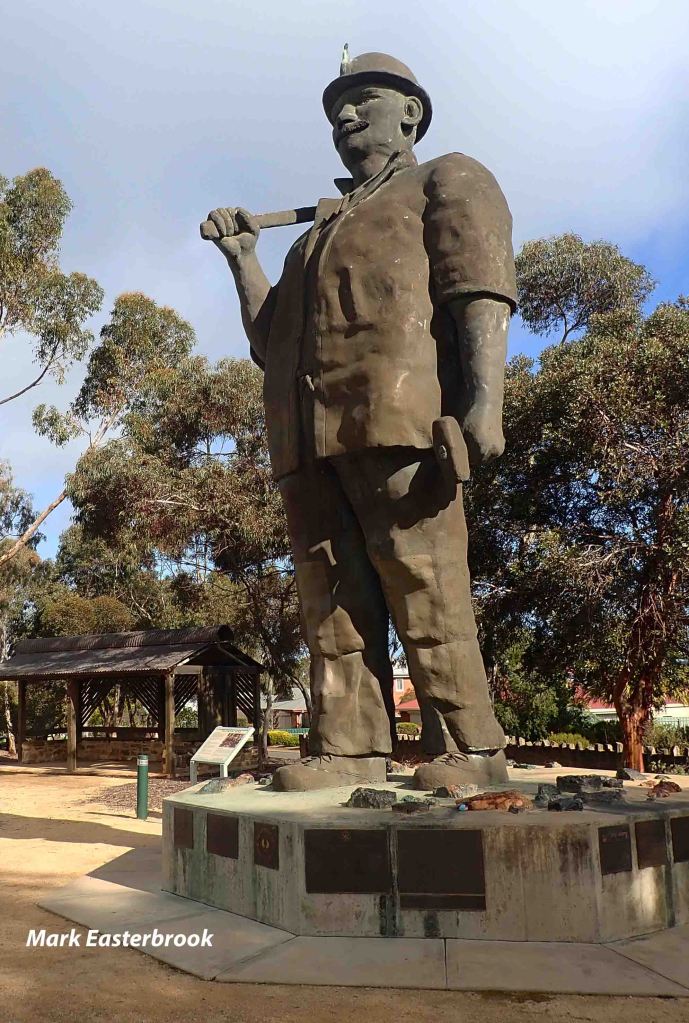

We stopped off at Map Kurnow in Kapunda. A large statue to the Cornish miners that travelled this route from Adelaide to Burra between 1845 and 1877, chasing work and copper.

Further down the road was the Marrabell Rodeo, with its statue of Curio, the Brumby famous for throwing even the best riders. The statue celebrated the successful 10 second ride of one such horseman in 1850. The route to Burra has examples of life within the copper rush era, representing activities along the supply chain between Adelaide and Burra.

Picking up the Burra Passport on the first morning, our Norwegian informer inspired us with descriptions of the sites to see. A novel idea, tourists buy a Burra Heritage Passport, basically a key and booklet, that allows access to the refurbished or ruined landmarks of the area. Some were off limits, as it was difficult to meet the Covid-19 restrictions of single file, one way travel.

Thus the cellar of the Unicorn Brewery, and the museum were off-limits. Apparently worthy of a return when we find a vaccine for this virus and devise clever ways to exhibit historical artefacts in a socially distanced and clinical manner.

At the mine site we had a good view over ‘the Burra’, the collective name for neighbouring townships. Former mining company towns, the areas of Kooringa, Aberdeen, Redruth, Hampton, and Llwchwr, merged to called Burra.

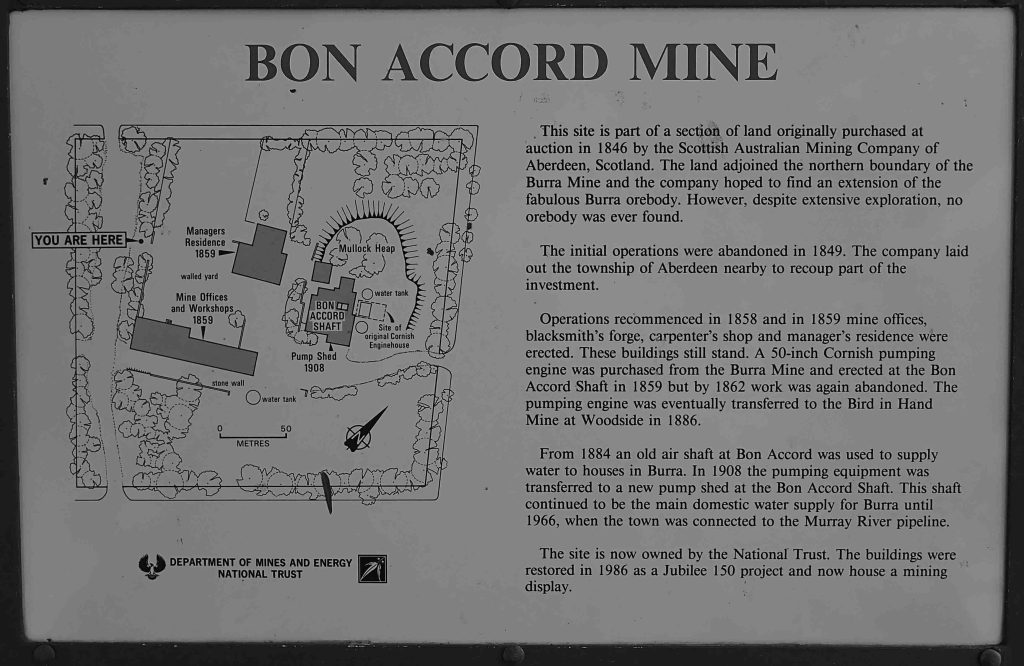

The signboards showed a map with the little township of Aberdeen off to the left. Fitting, as I was due to fly back to Aberdeen, Scotland, in three weeks. The township had been established by a group of venture capitalists who built the Bon Accord mine. On the right was the Burra Monster Mine created by the Nobs and the Snobs.

The Nobs were capitalists and pastoralists, who had formed the Princess Royal Mining Company (PRMC). The Snobs were a group of Adelaide shopkeepers and merchants, who formed the South Australian Mining Association (SAMA). A lease was drawn up in 1846 around the known copper outcrops, with the Nobs claiming the southern half, and the Snobs the northern half. The Aberdeen based group arrived later and claimed a small section in the north west.

Cornish miners were encouraged to set themselves up in the new community and use their valuable skills in the mine workings. The Welsh were brought across to run the smelting works. The Burra was a melting point of diverse communities in its heyday. People escaping economic decline in Cornwall and Wales, or hoping to strike it rich quick.

The Burra mine, owned by SAMA, struck a valuable copper ore body and operated between 1845 and 1877. The Bon Accord mine did not find a commercially viable ore body, and partially closed in 1849, abandoned in 1862. The Nobs also had little success and closed in 1851.

Amazing, over a distance of less than 500 metres two companies go bankrupt whilst one flourishes. Geology is a cruel mistress. The SAMA lease went on to be Australia’s largest metal mine up to 1860, when it was overtaken by developments from the gold rush in the eastern states.

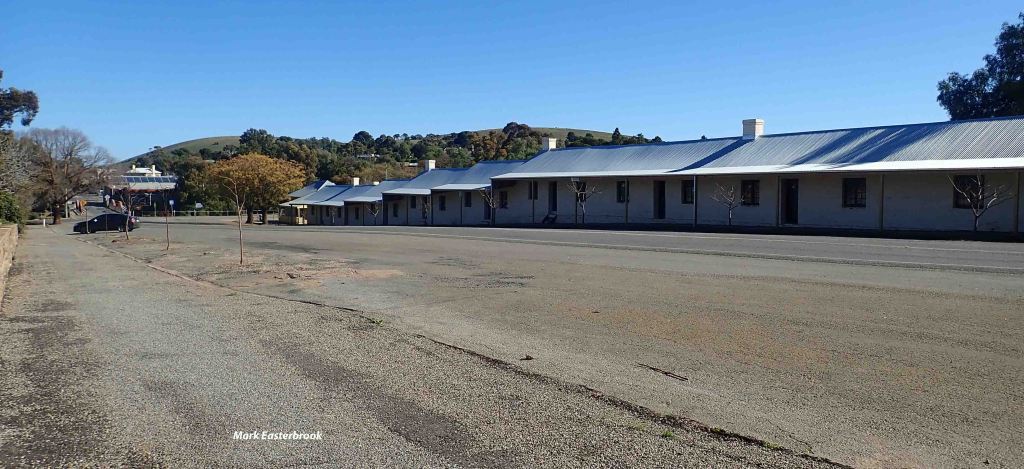

The owners of the Bon Accord Mine had to recoup some of their costs and built the township of Aberdeen on its licence. Successful miners working on the Monster Mine bought residence here and the Aberdeen community developed.

Significant infrastructure was built on the wealth of copper during the boom years. The mineral wealth saved Adelaide and the fledgling colony of South Australia. Almost bankrupt in the years since founding by William Light and Governor Hindmarsh on 28 December 1836, the colony needed an economic boost and quickly. The Burra Monster Mine certainly achieved that.

Standing on top of the mine workings, looking out from the Morphett Engine room, home to the large Cornish Beam Pumping Engine, with imagination the site comes alive with the sounds of the past.

Mining returned to Burra in the 1980’s, stripping the overburden and boosting the economy for an additional 10 years. The resulting deep open pit, now filled with water, serves a new purpose, that of a deep water dive training school. Triggering memories of Saturdays diving in the Buchan quarry, just outside Aberdeen Scotland, when the sea state was too rough to dive in.

The lands around Burra developed in parallel as sheep farms and cropping, with much of the produce being sold to feed the people of the gold rush in Victoria and New South Wales. Mining was the biggest industry in town throughout the life of the Monster Mine, but agriculture was developing and became the mainstay of the town once copper mining became uneconomic. If mining saved South Australia, and kick-started Burra, then agriculture provided longevity.

In 1865 George Goyder was sent to map the lands in the emerging state of South Australia. His observations lead to the Goyder Line, areas north were deemed drought prone, those south were arable. Running through Burra, this town became a demarcation between cropping and pasture.

Looking through the miners housing brought back favourable memories of my time in company accommodation. Ar Ratawi (Basrah), Panaga (Brunei) and even Zima 3 (Sakhalin), were all top quality in comparison. Of the many people who arrived in Burra, some 1800 had no place to live. So they dug in to the sides of the creek, housing their families in the hovels, where typhoid and flooding were frequent worries.

Those lucky miners in the middle pay-scale could spend a third of their salaries on rent and get a lovely little miners cottage in Paxton Row. Walking through the cottage, for this miner and his family, the children had safe places to play, and wives had a social structure to enjoy, life down the mines would have been more bearable. Now featuring on Booking.com and Tripadvisor, these and other quaint cottages support the growing heritage tourism and weekend getaway accommodation market.

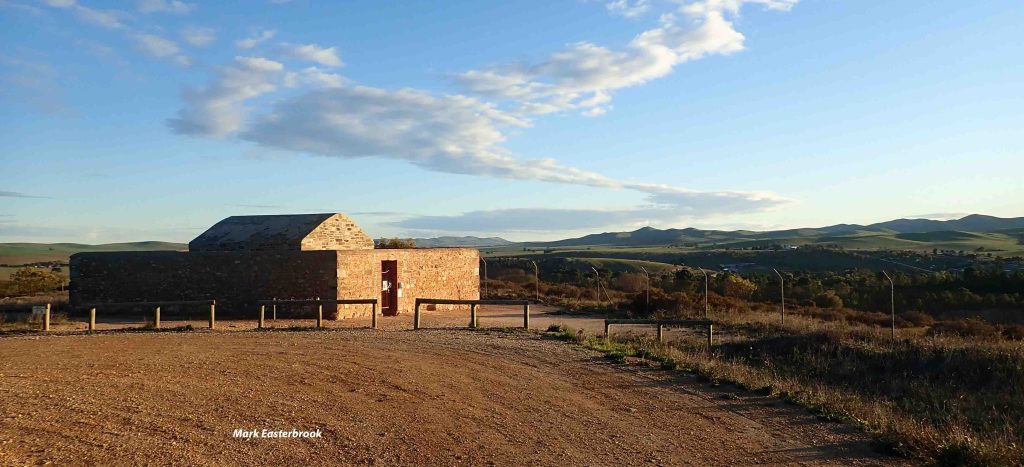

The Hampton miners cottages present a picturesque image of dry walled foundations perched on a hill with a view to the mine. With the colours of the late afternoon sun, the site comes alive with the sense of community that existed in the area. With the last resident leaving in 1960, the cottages would have been home to many, despite no electricity or running water. Walking down the streets of Llwchwr, Welsh names, lacking any vowels, show a community trying to remember the towns of home, whilst striking for themselves a new life under the South Australian sun.

By 1877 the copper price crashed and the Monster Mine was left to develop low grade metaalliferous ore, by the open-cut mining method. Unprofitable, the mine closed in 1877. Pushing some 1000 workers and the associated service industry in to unemployment. Some turned their hand to farming, others chased the minerals industry around Australia, others remained to eek out a living in the declining community.

Some believe that North Sea oil saved the political career of UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher in the late 1970’s. Just as the political career of Governor Hindmarsh had been saved by Burra’s mineral wealth. The Scottish town of Aberdeen boomed throughout the latter part of the twentieth century on the back of oil, building important infrastructure. Now that oil prices have fallen abruptly, and look to remain low for years to come, workers in the oil and gas community are looking for ways to survive the transition in to the next economic driver.

This oil price crash has displaced many workers, with the energy majors and service suppliers cutting projects and hence staff. A large migration of a displaced international oil and gas workforce returning to their bases has started, just as in 1877 with the Monster Mine closure. Some are looking to transition into other industries with a more certain future, others keep their fingers crossed their jobs in associated areas will survive the present crash.

In 2006 I rolled in to Aberdeen, Scotland, a bustling town that had done well on the back of the oil industry. Returning in 2016 during an oil price slump, it was clear to see the heydays were over. My return in 2 weeks time, triggered by a significant crash in the oil price and fundamental changes being undertaken in the industry, will be an eye opener.

Ambling along the streets of Aberdeen, South Australia, it is encouraging to see the variety of uses of the town infrastructure over the last 150 years. Buildings passed hands from grocers, fruiteers, public houses, private homes. The railway had developed then declined, farms had grown. Many miners cottages still looked well cared for and lived in. Despite the loss of the first industry that saved the South Australian state, the town of North Burra (formally Aberdeen) continued to flourish as it transitioned and diversified its economy.

As an aside, the area has been home to living creatures for many years. Fossils of Diprotodon, the worlds largest marsupial, are found in the soils. As the former lake bed erodes, fossils are being unearthed. The ‘Landscapes of Change’ trail is an excellent walk around the former lake bed, in search of this wombat from the Cenazoic era.

Back to recent times, Burra developed during the age of mining. The buildings and stories left behind by those who earned a few pounds during the mining era, are special. AJ & PA McBride’s, one of Australia’s largest wool suppliers started life here in 1902. Using the money earned from a life at sea and down the mines, at the very young age of 25, Albert McBride built the Mcbride cottages and contributed to the new industry in Burra, wool.

The main shaft of the Bon Accord mine had struck water during its time of operation, and a very large Cornish-built pump was installed to keep the miners heads above water.

In 1908, many years after closing the shaft, it was identified that the water was suitable for drinking. The shaft became the town water supply until 1966, when the town was linked to the Murray River water system. Recycling of mining era infrastructure provided Burra and Aberdeen a spring-board into the next major industry to employ the people of the region.

My morning run took me past the smelting areas and around the copper mine workings. Bringing back memories of working at Rio Tinto’s Northparkes Copper mine and the Richards Bay Minerals titanium mine. It is fascinating to see the earliest trials of the technology we used, some hundred years later, to mine copper and smelt titanium. Memories of having played a part in the history of the minerals industry in both Australia and South Africa, filled me with pride. The chill of the winter morning breeze shook me back to the present.

Soon I’ll be returning to Aberdeen, Scotland, hopeful of finding employment in the UK Energy Transition initiatives; the present push to make our energy production and usage more efficient and cleaner. With significantly fewer jobs in the industry and many displaced people competing for them, the future is uncertain.

The alternative is to cash in my time with the company and snoop around for the next Albert McBride, emerging industries, or towns like Burra, that through adversity chart a new way forward.

Whatever the future holds, we sure have had an exciting past. Drawing on knowledge and skills of a global workforce we’ll find a solution to this virus, our need for clean energy and resources, and build a robust and stable economy. Fingers crossed Boris Johnson, Scott Morrison and Cyril Ramaphosa build a good framework to allow those industrious people the space to develop the new technology for future industries to establish and prosper.