We spent a night recuperating at the EHRA Base Camp in Namibia’s Kunene region, following an energetic few days building an elephant defence. By 8 am we rolled out of camp, for the start of Tracking Week.

Searching for an elephant herd, assessing their health and observing their behaviour, was the goal. Observing their interaction with the local communities was a potential, but that story had not been written as the wheels started to move.

Passing the ANIXAB school (A. Gariseb Primary School), with its fascinating murals painted on the walls, we took a sharp right and entered the Ugab River. Big Matthias exuding enthusiasm, engaging with all the people we passed. Rounding the bend in the river we saw Voortrekker, the area’s famous old male. Now no longer with us, it was fitting that our first elephant sighting this trip was old Voortrekker.

Further downstream we met the Mama Africa herd, named after the former matriarch from a decade ago, grandmother of the present herd.

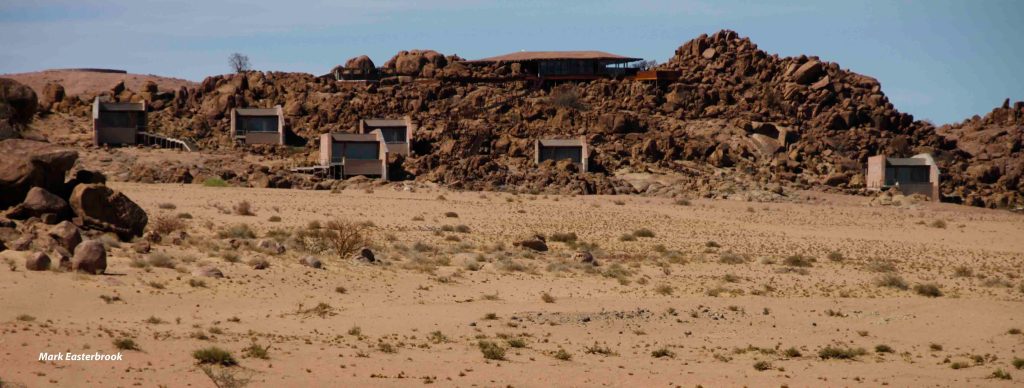

The plan was to meet our guide, Marcus, at the Brandberg White Lady Lodge. An oasis in the desert, lodges are a key component of the Conservancy Model. A primary source of foreign income, and a welcome luxury in the sparse landscape.

Marcus was a breathe of fresh-air. Local Namibian, with a foreign Masters degree education, his knowledge of the area was broad, but deep, and delivery infectious. The offer to ride up front with him was floated, and I took the opportunity immediately.

Big Matthias found an elephant track and pointed confidently in the direction that we started to move. Our guides were confident the animals were heading to an elephant dam. Built by a lodge to provide water to elephants and to provide tourists easy viewing opportunities of these great beasts. We arrived at the site and waited. About 15 minutes later, we saw dust rising in the distance and the herd of elephant pierced through the tree line. Walking calmly towards the tank, they just kept coming, easily 15 of them crowded round the tank.

Within 10 minutes they had drank their fill and moved on, but not before they had soaked themselves and the soils around the tank. Looking behind us, the rooms at the lodge have a great view of this very enjoyable, but somewhat infrequent encounter.

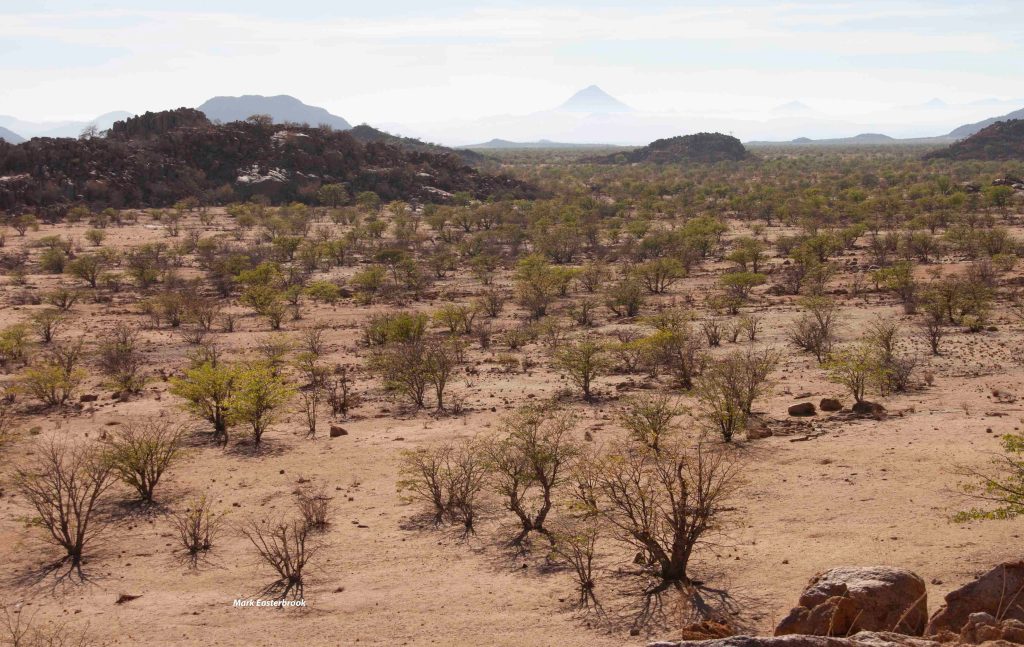

The green trees indicated that there was ground water in the area, however it may be too deep for the elephants to dig down. Apparently this herd was heading further downstream, where the ground water nears the surface during the dry months, and flows out in natural springs.

Driving to higher ground, we found ourselves a campsite, rolled out the tarpaulin and settled down for dinner and a night under the stars.

It was a cold night! Whilst we slept, the dew condensed from the famed Namibian mist rolling in from the sea, all over our sleeping bags. We were only 50 km from the coast, the air was moisture laden, but unable to rain. It was much cooler than Base Camp, some 100 km inland.

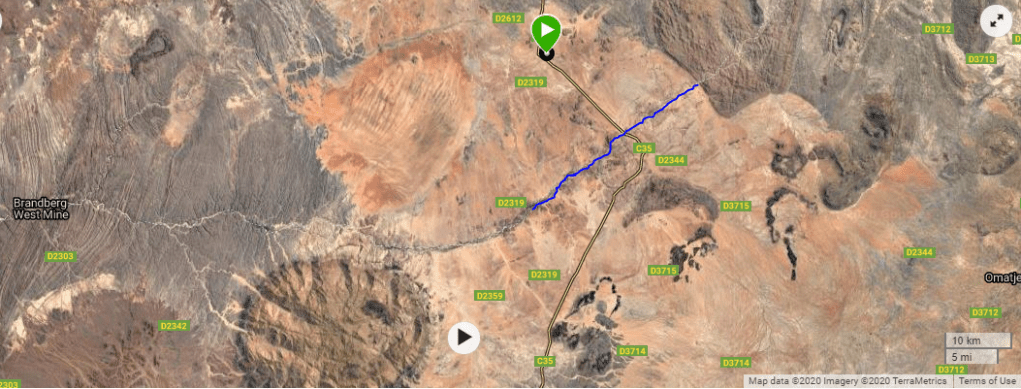

Marcus indicated that our mission had changed overnight. Rather than progressing down river to find the ‘Ugab Small’ herd, we would track another herd that had been reported damaging fences and trampling goats. The base at Swakopmund had contacted us, outlining where they were. We got into the trucks, rolling out of camp by 8 am.

We had driven 2½ hours by the time we arrived at the affected farmhouse. We were introduced to the female president of the Conservancy, whose goat had been trampled and whose fences had been damaged.

A fence post had been knocked down by an elephant and a goat had been trampled in the excitement. Through scattered conversations it was apparent that under the Conservancy conditions, residents are compensated for loss of livestock resulting from elephant damage.

The EHRA team tracks the elephants to assess elephant behaviour, indirectly attempting to understand why the damage had been done. Records were taken at the scene, all agreed that the fence posts were not damaged, and could be re-positioned.

By assessing the tracks, Big Matthias concluded it was caused by one of the younger males of the G6 herd. We returned to the vehicle and followed the tracks. The aim was to track the herd, observe their behaviour and determine if the animal was in distress.

It was difficult to understand goat ownership protocols in the Kunene Region. From scattered conversations it appears that goats are held more as pets, a throwback to the history of the community as goat farmers. A business that the members of this Conservancy no longer engage in, but they keep the animals as a living memory. Hence the loss of a goat was not associated with a loss of livelihood or sustenance. But compensation for its demise was still expected. An interesting evolution of a tradition to be investigated on future trips to Namibia.

We drove back to the Sorris Sorris sign and community members called out to us, energetically pointing in one direction, presumably pointing to where the elephants went, their energy indicating that the elephants had recently passed by.

We zigzagged off-road, following their tracks, but it was difficult to determine direction. We came across a farmer who said that the elephants had come by last night, and broke down the fence of his neighbour, who had given up on farming and sold his goats soon after. A very quick decision I thought, hence my interest in understanding the role that goats played in the community.

We saw that the fence had been pulled down and the goats had escaped. Big Matthias indicated that it was the same elephants who had damaged the other fences, most likely the G6 heard, and we gave chase on the tracks.

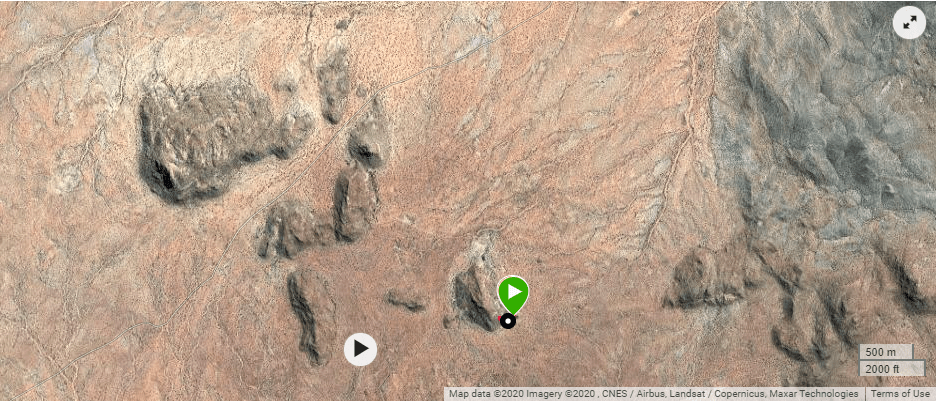

These tracks zigzagged, and were difficult to follow. We needed to view the land from up high. We found a hill and climbed on foot to view the area, but had no luck in spotting the herd. Following the tracks further, an hour later we climbed another hill and hey presto, elephants were seen on the horizon.

We jumped into the vehicles, headed for the distance, and soon laid eyes on the G6 herd. Thankfully there were no visible signs of injury or distress. The young male was sighted, and he did appear nervous, but this was put down to natural adolescent male behaviour. We watched the herd for a while, with Marcus outlining what made them a desert adapted elephant.

They are the same species as the African Elephant, Loxodonta Africana Africana, but these ones can go longer periods without drinking, two days. They have a larger home range as they need to travel further for food and water.

At about 17:00 we found a new campsite. At the foot of a kopjie, an Inselberg. Enjoying a glass of wine, from a tin cup, the evening colours were stunning.

The night had been cool and crisp. Waking with a thin film of moisture on my sleeping bag, it was clear to see how the sparse vegetation is able to survive in this ‘dry environment’. We had our items packed and were off by about 8 am. A message had come through from base, the farmer who gave us the directions yesterday had reported elephants breaking his water pipes today. So we went to investigate.

At site we were met with a scene of wet sand around the tank and elephant wall. Quickly collecting the facts, Big Matthias and Marcus concluded that the elephant herd we saw at sunset had returned during the night. They had moved past us whilst we slept. They arrived at the tank early this morning and did the damage before heading back towards the river.

The ground around the wall was wet. The elephants had smelt the water through the pipe, dug it up and pulled it, breaking the connection to the tank. The stored water had flooded the area within the wall and ran outside.

The goat trough nearby and the modified agricultural dam did not provide the herd sufficient access to water. So they had found a shallow buried pipe and pulled. Breaking the connection and spilling the community water.

In what was a very heated discussion, the people gathered, and accused Big Matthias that ‘his’ elephants were causing problems. The elephants should be relocated to Etosha National Park, was the repeated line. In my limited knowledge of Afrikaans, I heard Big Matthias say that they are not his elephants, they belong to the community, referring to the Conservancy model we had signed up to.

It had been recommended to bury the pipe 50 centimetres deep; it was buried 5 centimetres beneath the surface. Easy access to passing elephants.

There was an agricultural water tank nearby, converted to an elephant drinking dam, which was too high for the younger elephants to reach. When the elephants came to the site, they couldn’t reach the water in the open tank. With insufficient water in the goat trough, and poor access to the elephant tank, the animals had pulled the pipes out of the existing tank to get the water.

EHRA had scheduled work to cut the walls of this concrete water tank to a lower height to allow the smaller elephants access to water. But, due to a high demand for other work, the resources to complete the activity were not available.

There was a comment about money, from a community member along the lines that EHRA should pay for the damage. Big Matthias countered by saying that EHRA was not a government organisation, it is an organisation primarily funded by volunteers.

It was interesting to be bought in to the conversation, as I had been slightly uneasy with the concept of two truckloads of majority Europeans arriving in to a local Namibian community to look around their property, take pictures and listen to their stories. I wondered what my role was in this story, and whether it would be accepted by this community.

With the attention on us, our role was clear. We are a funding source in the Conservancy Model, and we were being given the opportunity to see first-hand how our funding goes to work. In an attempt at bridging the gap, one of the confident locals asked us what we thought the solution was. Unable to choke together a semi-intelligent, unified answer, the conversation drew to a close.

It was agreed that an angle grinder was needed to cut the elephant dam to size. If the elephants can drink from a suitable sized elephant tank, they will not need to dig up the pipes. Another solution found. The challenge was now to find the funding, find a resource to do the job, and schedule the work. Not as easy in practice in this remote region.

Big Matthias reiterated that EHRA is here to support the community, providing solutions to live alongside the elephants. A community member challenged, saying if you weren’t here, there would be no elephants. Elephant populations are growing, bringing more tourists, resulting in a change to the subsistence lifestyle. With the scene in front of us, the frustrations within the local community towards ‘their’ elephants was understandable.

We moved on, hopefully with a solution, found another stunning campsite and enjoyed dinner, sunset and a good read of my book. This was our last camp in the field and it was a beautiful place.

Three key geological features were present, granite intrusion, basalt layering and some very well metamorphosed slate. When we climbed the mountain to look up at the Brandberg, we also had a great view of the beginning of the slate feature that forms the backbone of the Skeleton Coast, heading northwards for 700 kilometres.

During the night one of our team members had heard scratching around his swag. Asked if we heard anything, we all answered no. Rolling up the swags after breakfast, the culprit scampered away. Sharing the warmth of a scorpion certainly counts as a unique experience! Staring in to the eyes of a desert-adapted elephant, even more so.

We made our way back to the Ugab River and in the early light of the morning, our experience moved from inspirational to exceptional. Two desert-adapted lions crossed our path, walked with us a while, then clambered up the slate lined hills. Watching the agility of this animal, confidently climbing the mountain-side put a smile on our faces that would not be washed off that day. To think, we had been camping just two valleys over! It is easy to reflect positively on the great experiences that life has to offer when in this environment.

It was a long journey back to the river from the plains. Past the old commercial farming areas that had been turned over to small-holdings now. Passing through a moonscape, we came across the plant that had been on the cover of one of my primary school geography books, some thirty years ago during my South African life. The Welwitshia plant can live up to 600 years. Its long leaves collect the dew from the morning mist and funnel the water to its large tap root. Condensing water just like my sleeping bag these last few nights.

This was the image of Namibia that I had wanted to catch with my own camera. Snap, return to the vehicle, to head home. But we had one last detour to take, heading back to camp via the Ugab river in an attempt to find the ‘Ugab Small’ herd.

We reconnected with the Ugab, having completed the journey that most elephants do at least once a year. A round-trip from the river, to the inland plains, during the wet season, then return to the permanent water source of river during the dry season.

It was a very long drive from the moonscape scenery of the plains to the surprisingly lush vegetation of the river bed. In an unexpected ending to two weeks in the desert, we had to push the game vehicle out of a muddy puddle when it bogged. Requiring a tow from the lead vehicle, it was comforting to see so much water available even during the dry times.

My only hope is that the rains recharge this ground water system, and the large volume of water being drawn from the water wells is managed, to maintain the aquifer water that mitigates human-elephant conflict.

Back at camp, we were thankful for the experience to peek into the lives of the community living alongside desert-adapted elephants. The Namib, certainly a unique Ecosystem Hotspot!

Written by Mark Easterbrook

This is an unpaid blog post. It is written to reflect on a very positive life experience and written to record these memories for myself to reflect on at a time when memory fades. It provides a positive view on the organisation EHRA, as without them, this experience would not have been possible. Their work in Namibia is an inspiration. You are invited to review, interpret and comment on these thoughts. Discussion will enable me to place these personal memories in to a global context. Wishing you well on your conservation and social development journey in global Ecosystem Hotspots.